UVA Innovator of the Year Marc Breton’s Surprise Journey to Diabetes Pioneer

Jan. 31, 2023

Having earned his Ph.D. in systems engineering from the University of Virginia in 2004, Marc Breton was all but certain he would be returning to his native France to begin a professional career, play a little rugby, and, with any luck, start a family.

A confluence of circumstances changed everything.

At the time, employment conditions in France for young researchers like Breton weren’t good, and a large social movement around the issue was in full swing.

It was also around that time when Breton – through UVA engineering professor Donald Brown – was introduced to School of Medicine professor Boris Kovatchev to help apply a mathematical model to attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder data that Kovatchev’s team was working on. It led to Kovatchev offering Breton a postdoctoral position to work on his diabetes research project.

While working within the medical field had been the furthest thing from Breton’s mind, the decision to stay at UVA actually didn’t prove that difficult.

“It was stay here and have a job with someone I’ve enjoyed working with, and in a subject that could be interesting and I don’t know much about,” Breton recalled, “or I can go back and try to find a job in the middle of a social movement.”

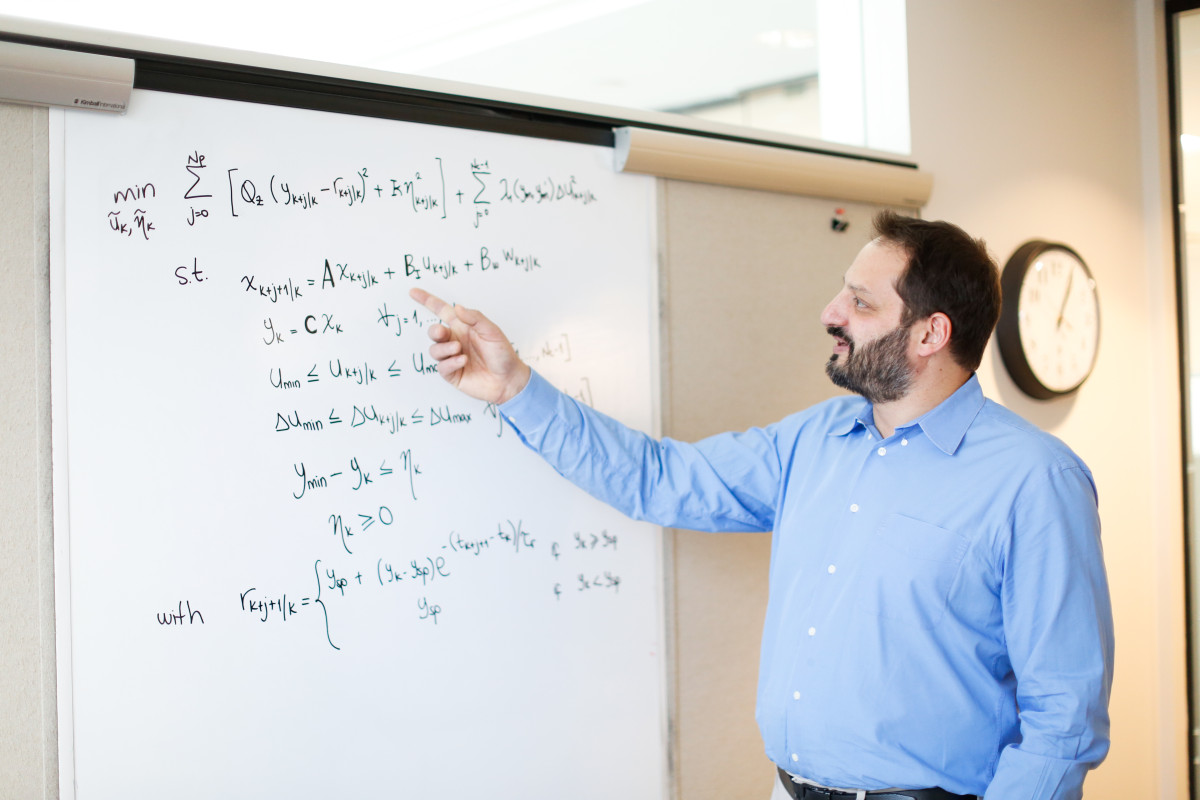

Teaming with Kovatchev, Breton went on to create the first – and to date only – simulation environment accepted by the U.S. Food & Drug Administration as a replacement for animal studies in pre-clinical assessment of insulin treatment strategies. It paved the way for the pair’s invention of a revolutionary artificial pancreas that could monitor and automatically regulate a person’s blood glucose levels.

Today, the work that Breton started when he was a post-doc nearly 20 years ago continues to improve the lives of people with diabetes around the world.

It is for this reason that UVA Licensing & Ventures Group Executive Director Richard W. Chylla said Breton was chosen as the recipient of the 2022 Edlich-Henderson Innovator of the Year award. The endowed award recognizes University faculty members or a team of faculty researchers whose work is making a major impact on society.

“Here at UVA LVG, our mission is to grow and guide University innovations, but equally important is to make a positive impact on society at large,” Chylla said. “If you look at the total return on Dr. Breton’s work at UVA – the lives of patients improved, the jobs created, the continuing sponsored research and the royalties back to the University for research reinvestment – it is a testament to this mission. Dr. Breton’s work deserves this recognition, and we are proud to celebrate him.”

Kovatchev says Breton, an associate professor in psychiatry and neurobehavioral sciences in the School of Medicine, is one of a kind.

“Marc has a unique ability to see, compartmentalize and solve problems,” said Kovatchev, the co-founder and director of the Center for Diabetes Technology. “This is a rare combination, and it drove him to this success.”

Early Days

One of three children, Breton grew up in Paris. His mother worked in academia, specializing in in microbiology. His father was a high school and college biology teacher.

“There was an expectation in our family that you shall do good in science, and you shall pursue long studies,” Breton said with a laugh. “I never got a sense there was another option. There was an expectation of education.”

Breton often accompanied his mother to her lab. Her research centered on malaria and how parasites invade red blood cells.

Over the years, Breton overheard his fair share of seminars, and this made him pretty sure he never wanted to follow in either of his parents’ footsteps.

Breton jokingly called himself the “black sheep” of his family because he was drawn to math and engineering, in contrast with the long family tradition in medicine and biology. From an early age, he enjoyed trying to understand how things worked. As a 10-year-old, Breton remembers trying to create three-dimensional shapes with pieces of paper.

“I’ve always loved solving problems … the figuring out of how to get from point A to point B – or even that there is a point B to get to,” Breton said.

Still, Breton had no idea what he would do with his skillset, how he might be able to someday parlay his love for math into a career.

In the meantime, he played rugby.

It was while in France earning his undergraduate and master’s degree in engineering – with a specialization in automatic control – when Breton picked up the sport. He joined his school team and has played, coached and refereed ever since.

“It’s been an outlet,” Breton said. “That release has been something that has kept me sane.”

Changing the Game

After returning from a conference in 2006, Kovatchev told Breton about someone at the event who believed the idea for an artificial pancreas wasn’t possible. “That is the best way you can make Boris do something,” said Breton, smiling. “He came back and we started working on it.”

The big question was whether sensors could be used to dose insulin.

Neither Breton nor Kovatchev had any experience in animal models or research, which left them in a bind since they needed to generate data that could show that what they wanted to do was safe for humans.

Amazingly, Breton and Kovatchev’s team found a work-around. They created a computer simulation that could replace animal testing. And when the FDA approved it, it was a game-changer for diabetes research. What once took five to 10 years now only took a couple months.

“All of a sudden you could go and test something on a computer and then test it in a human being a few months later,” Breton said. “We completely bypassed that whole step.”

In 2008, the first human clinical trial of the artificial pancreas commenced under the guidance of Dr. Stacey Anderson.

“It was awesome,” Breton said. “There were some grueling sessions where you don’t sleep, you’re stressed out trying to make sure everything is working because you don’t want to hurt anybody, but it was incredibly exciting.

“I loved getting real data, not just playing with a computer – actually running clinical trials with human beings and talking to them. For an engineer, it was pretty awesome.”

The device, at that point, was primitive. With long cords and a clunkiness that made transport difficult, it was, in Breton’s words, a “Frankenstein lab monster.”

But in 2012, Breton and Kovatchev, with former UVA faculty members Steve Patek and Patrick Keith-Hynes, figured out how to program their algorithm into a smartphone.

“Now we had a device that was portable,” Breton said. “There was a hint of, ‘This could be real. This could be something that people could use.’ They could have an app on their smartphone that controls their insulin pump.

“That got us thinking that this wasn’t completely an academic exercise anymore.”

Enter UVA LVG.

The University’s technology transfer office connected the team with two of its entrepreneurs in residence, Jeff Keller and Chad Rogers, who, in turn, helped them obtain patents for the device and form a startup company called TypeZero Technologies.

Soon after, TypeZero and its six co-founders were able to license the device, now known commercially as the t:slim X2 insulin pump with Control-IQ, to Tandem Diabetes Care, a pump manufacturer.

In 2018, TypeZero was purchased by DexCom Inc., the leader in glucose monitoring for people with diabetes.

Today, the fruits of Breton’s labor are helping people with diabetes everywhere.

“Our little algorithm is now probably in 400,000 devices around the world, controlling the insulin of 400,000 people from the age of 2 to 98 years old,” Breton said, “and that’s very special because I had the opportunity to meet many of these people and hear how this work has impacted their lives. That has been an incredible high.”

Breton looks back fondly on the ski trips and visits to summer camps that he made in order to test the device in high-energy environments with kids from across the country.

So do the kids.

One of them, Benjamin Motta, was so impressed by Breton that he came to UVA and is now working as an intern at the Center for Diabetes because of him. For his undergraduate admissions essay, the Fredericksburg native wrote about how much Breton and his colleagues inspired him.

“They are not just a bunch of faceless lab scientists who make new discoveries,” said Motta, a third-year student in the School of Engineering and Applied Science. “It’s people who genuinely want to make a difference in the world and how other people are able to live, and who have a genuine fascination with the science behind it all. Seeing that, and especially how it touched my own life, was life-changing.”

Motta recalled the first time he tried a version of the artificial pancreas while on a ski trip with Breton. He had struggled with variable blood sugar ever since he could remember, but now suddenly – despite several hours on the slopes and a meal – it was static.

“It was like magic. It was extraordinary,” Motta said. “As a 12-year-old, it was fascinating to see that kind of engineering happening live … it was incredible.”

To this day, Motta is benefitting from the algorithm Breton helped develop.

“I’ve never had better blood sugar control in my life,” Motta said, “and I know I’m not alone. Marc is making lives better for a massive swath of people across the world.”

Innovation Never Stops

Following the creation of the simulator and the artificial pancreas, Breton helped develop another algorithm that gives patients an idea of how well they are doing between doctors’ visits by providing a precise estimation of their hemoglobin A1C (a key indicator of long-term glucose control). The algorithm took Breton just two weeks to complete, and it was implemented into MyStar Extra, the first commercial blood glucose monitoring device capable of estimating A1C from fingersticks.

Overall, Breton has submitted 55 invention disclosures to LVG since 2007, and he is a named inventor on 27 issued U.S. patents.

“Dr. Breton is one of the University’s most successful inventors, and the technologies he has developed throughout his career have saved and improved countless lives,” UVA Vice President for Research Melur K. Ramasubramanian said.

While sitting in his office at UVA’s Center for Diabetes Technology – which he co-founded with Kovatchev, Anderson and Patek in 2010 – a smile crept across Breton’s face when asked what he hopes to accomplish next.

“One of the glories of academic research is that we’re never done,” he said.

Recently, Breton and Kovatchev finished a clinical trial for the next generation of the t:slim X2. By tweaking parts of the original algorithm, they have created a full closed-loop system. This means users won’t need to ever interact with the device. They can, in Breton’s words, “just set and forget” it.

“If you don’t have to interact with the system, you don’t have to train on the system and think about your diabetes all the time – that’s a big thing for people with Type 1 diabetes,” Breton said. “It’s also potentially a big deal for people with Type 2 diabetes, because if you have a simple system that you can just set and don’t have to do anything with, well then it becomes a valid therapeutic solution for broader populations.”

Breton aims to not only provide full automation for patients, but to be able to give more guidance to physicians.

“There’s a whole lot of data in diabetes and it’s a shame we’re not using it,” Breton said, “so our mission here is figuring out ways to use all of that data for the betterment of patient care, health system efficiency and also potentially informing companies of technologies they should be pursuing.”

Breton’s work epitomizes UVA’s commitment to biotechnology and its promise of saving and improving lives. UVA recently announced plans to launch the Paul and Diane Manning Institute of Biotechnology, which will transform health care in Virginia and beyond with its focus on biotechnology research and development of modern treatments and cures for disease. Ironically, the Mannings provided early funding for the artificial pancreas.

“We live in a time of exciting possibility in health care, with new treatments showing great promise to help patients and their families,” UVA President Jim Ryan said. “UVA is right on the front lines of this work, and this recognition for Marc Breton is well-deserved. I’m grateful to him and his colleagues for what they have done to improve the lives of so many who are suffering from disease, including diabetes.”

Breton said he is humbled to have been selected as the Innovator of the Year, alongside past winners like Dr. Amy Mathers, Dr. Rebecca Dillingham, Karen Ingersoll, Lee Ritterband, Dr. Jeffrey Elias and Kovatchev.

“What a ride,” said Breton, who lives in Charlottesville with his wife, Emily Whipple, and their three children. “It’s incredibly rare for scientists to see the product of their work and have an impact that they can see on society. Usually, if you’re very lucky, you will have an impact after you retire.

“We got on a crazy train and got to see it immediately.”

UVA LVG’s 30th annual Innovator of the Year event will take place on Feb. 16, from 3:30 to 6 p.m., at the Rotunda. It will include a talk from Breton and a reception afterward. It is open to all UVA faculty, staff, students and community members. Click here to register.